INTERACTIVE FEATURES: When viewing this article on an electronic device, note that web addresses are live links. Just click the link to visit that web page.

Click for instructions for moving the PDF into Kindle, Nook, Apple iBooks, and Apple Library.

Don’t Miss Additional Easy-to-Access Links In This Article and Other Resources to Learn More

Plus, Three Strategies to Address Social Needs: Healthcare Positioning

Social determinants of health have been found to impact as much as 50 percent of an individual’s health outcomes. Given the flexibility in Medicare Advantage to provide additional benefits and to manage care holistically, there are opportunities for these beneficiaries to receive supportive services to address social determinants of health (SDOH), and to improve their health outcomes and overall health status.

A report published by the advocacy group Better Medicare Alliance looks at the role of social determinants of health in traditional Medicare and the Medicare Advantage (MA) program. It concludes that MA plans are well-positioned to tackle social determinants of health and the federal government should take that into account.

This report shows that MA is the choice for increasing numbers of enrollees with significant risk factors,” said Allyson Schwartz, president and CEO of the Better Medicare Alliance, in a statement.

- Nearly half of the lowest-income Medicare beneficiaries are food insecure. Among Medicare beneficiaries below the poverty line, 48% were in MA and 44% in traditional Medicare report not having enough money or food.

- 28% of MA beneficiaries living below the poverty line speak a language other than English compared with 24% in traditional Medicare.

- 18% of MA beneficiaries below the poverty line speak little to no English, roughly in line with 17% in traditional Medicare.

The report comes as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expands supplemental benefits for MA plans, including transportation benefits.

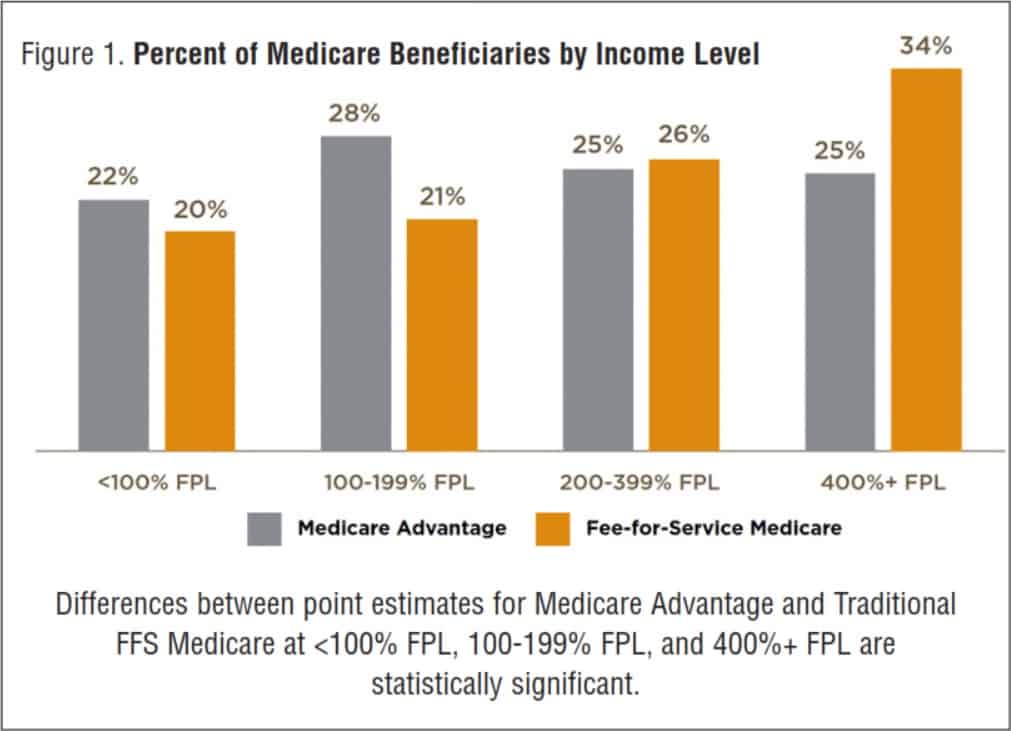

In general, Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are more likely than those in traditional FFS Medicare to be low-income, which impacts SDOH experiences. Approximately half of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have incomes below 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) compared with 41 percent of beneficiaries in Traditional FFS Medicare, and 25 percent have incomes above 400% FPL compared to 34% of beneficiaries in traditional FFS Medicare (Figure 1)

States are Looking to Medicaid MCOs To Develop Strategies To Identify And Address Social Determinants Of Health

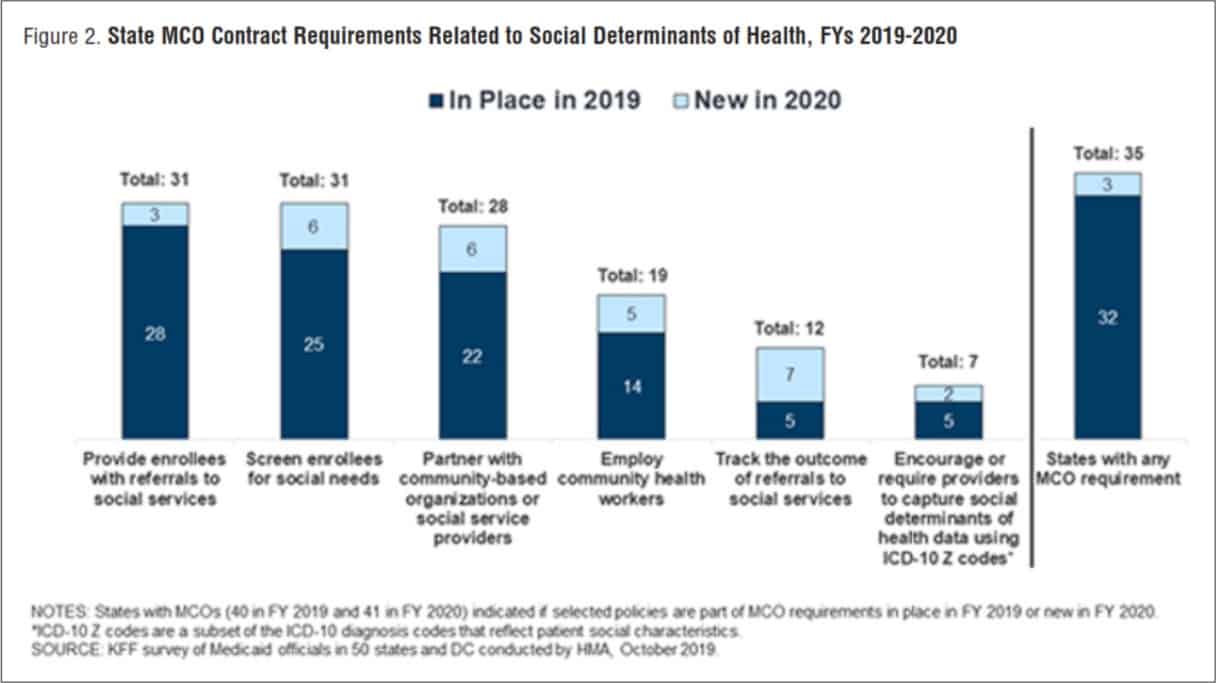

Many states are leveraging MCO contracts to promote strategies to address social determinants of health. For FY 2020, over three-quarters (35 states) of the 41 MCO states reported leveraging Medicaid MCO contracts to promote at least one strategy to address social determinants of health (Figure 2).

For FY 2020, about three-quarters of MCO states reported requiring MCOs to screen enrollees for social needs (31 states); providing enrollees with referrals to social services (31 states); or partnering with community-based organizations (28 states). Almost half of MCO states reported requiring MCOs to employ community health workers (CHWs) or other non-traditional health workers (19 states). KFF’s 2017 survey of Medicaid managed care plans found that a majority of plans were actively working to help beneficiaries connect with social services related to housing, nutrition, education, or employment.

Although federal reimbursement rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, plans may use administrative savings or state funds to provide these services. “Value-added” services are extra services outside of covered contract services and do not qualify as a covered service for the purposes of capitation rate setting.

In a 2020 KFF survey of Medicaid directors, MCO states reported a variety of programs, initiatives, or value-added services newly offered by MCOs in response to the COVID-19 emergency. The most frequently mentioned offerings and initiatives were food assistance and home-delivered meals (11 states) and enhanced MCO care management and outreach efforts often targeting persons at high risk for COVID-19 infection or complications or persons testing positive for COVID-19 (8 states).

Other examples include states reporting MCO provision of personal protective equipment (4 states), expanded MCO telehealth and remote supports (3 states), expanded pharmacy home deliveries (3 states), and MCO-provided gift cards for members to purchase food and other goods (2 states).

Social Determinants: Nine Payer & State Investments in Social Determinants

- Humana, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina (Blue Cross NC), and CareSource were among the first to announce social determinants of health investments in 2021.

- Humana is working with a few Ohio non-profits to tackle food scarcity and housing insecurity. The three companies that offer meals to Ohioans struggling with food insecurity are The Foodbank, the Greater Cleveland Food Bank, and the Mid-Ohio Food Collective.

- Blue Cross NC and the American Heart Association are offering around $100,000 in grant funds to support health equity in North Carolina.

- CareSource, a Medicaid managed care organization in Georgia, Indiana, and Ohio will invest $1 million in affordable housing in Oklahoma, where the payer is bidding for Medicaid business.

- Florida Blue Foundation, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Florida’s philanthropic arm, invested $9 million to support local organizations that focus on crisis management, mobile clinics, home care, and health literacy.

- Molina’s Community Innovation Fund pledged $1 million annually for three years, beginning in 2019, to fund community organizations that address SDOH for Washington’s Medicaid beneficiaries.

- Aetna’s philanthropic initiative, Building Healthier Communities, invested $100 million over five years to expand SDOH-related services and tools in its participating states, like Ohio, where it gave $2.5 million to organizations that tackle issues like opioid abuse.

- UnitedHealth Group has invested $400 million since 2011 into 80 affordable housing initiatives, creating over 4,500 new homes in underserved communities.

- Aetna invested more than $50 million to provide housing services to its Medicaid and Dual-Eligible Special Needs Plan (DSNP) members.

Payers are not the Only Entities Investing in SDOH

An article in Health Affairs by Horwitz et al. finds that by searching public announcements from healthcare companies and organizations involving direct investments, they identified seventy-eight such activities between 2017 -2019. This finding included 917 hospitals and involved $2.5 billion in health care funds. Additionally, the majority of these dollars went to housing-focused interventions. These facts attest to ever-increasing investments in social factors, in addition to identifying where many believe the strongest need resides.

A recent report from the Texas Health Improvement Network, funded by the Episcopal Health Foundation, covered ways to improve integration of services and other efforts to understand what is being implemented and make recommendations for future projects. The report highlights strategies for success.

Three Strategies to Address Social Needs: Healthcare Positioning

Link technologies with social sector partners. Technology that is integrated across health and social services systems is optimal. Platforms that enable health care organizations to screen patients for social needs and identify potential resources in their community are a good start, but the goal should be to integrate such software both with internal electronic health records and with databases and systems on the social-sector side. This will enable more effective hand-offs between the sectors, better tracking of outcomes and more coordination between health care and social services organizations.

More coordination will enable better outcomes. The most effective integrations typically involve organizations that provide both health and social services themselves. For other organizations, the more realistic opportunities arise from closer coordination among multiple organizations, including providers, payers and community groups. These can involve connecting referral systems; forming “umbrella” coalitions, which bring together stakeholders across multiple sectors around a common goal; and convening work groups focused on integration.

Grow your base of evidence. Documenting the effects of social determinants of health on individuals is immensely important, but so too is developing and documenting effective strategies for addressing social needs. Deepening this evidence base and sorting out what works will help make the case for why payers should shift more resources toward funding integration.