Over the past twenty years I have made over 31,000 house calls to more than 4,000 home-limited patients (patients with difficulty leaving their homes). House calls markedly improve the quality of life of home-limited patients and their caregivers while dramatically reducing healthcare costs.

With support from generous donors, the Home Centered Care Institute was founded in 2012 to help spread house call programs and facilitate integration of community resources on a national scale. The majority of home care medicine involves providing quality primary care to the most complex and costly patients in society. Modern technology also allows lab test, EKGs, X-rays, Ultrasounds, IVs and more to be done in the comfort of a patient’s home. Efforts have been made to spread home care medicine’s valuable mission but with limited success. Today, a perfect storm has developed that is fanning the sails of the modern house call movement. This perfect storm is made up of the six components listed below and will be thoroughly discussed in this paper.

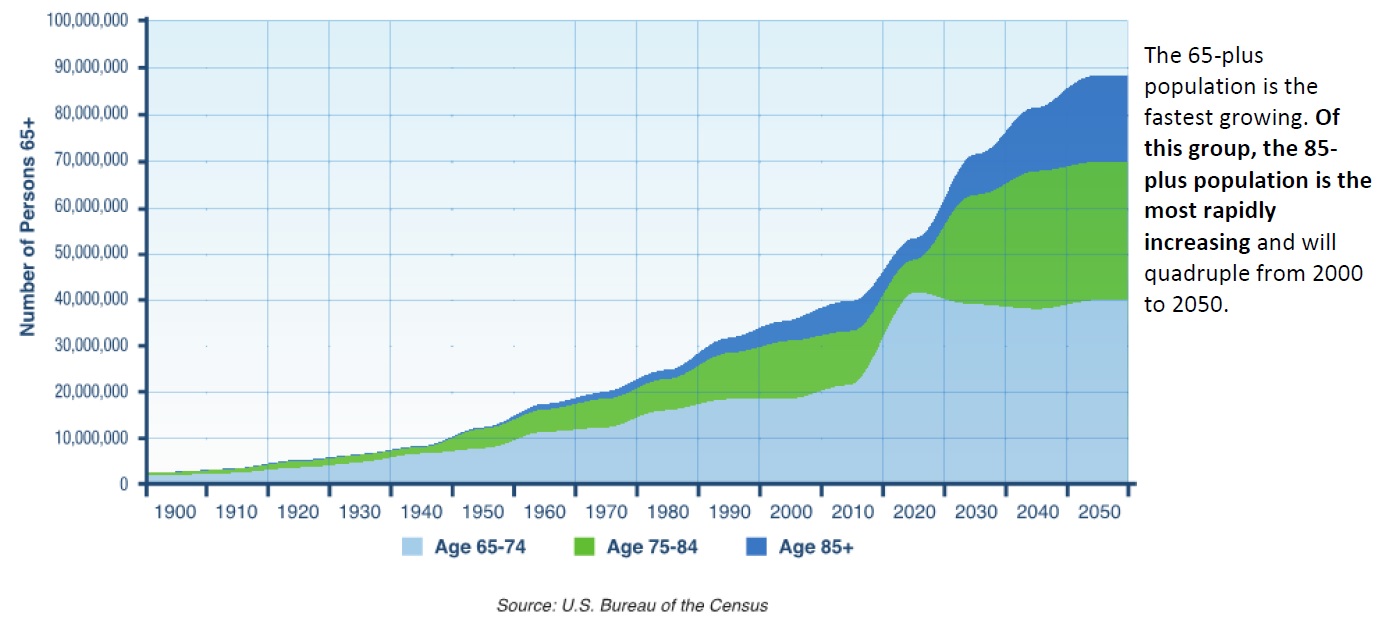

1. Demographics: The Aging of Society

As seen in the graph, the 65 years of age and older is the fastest growing population. The 85 years of age and older is the most rapidly increasing and will quadruple from 2000 to 2050. Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census. Copyright © 2015 by Home Centered Care Institute.

2. The Medicare and Medicaid Fiscal Crisis

3. Healthcare Reform: The Affordable Care Act

a. Readmission Reduction

b. Shift from fee-for-service “volume based” payments to “value based” payments through Medicare Shared Savings Programs (several Accountable Care Organization models) and the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative

c. Independence at Home Act house call Medicare demonstration

4. Federal rebalancing legislation including Money Follow the Person (MFP) and the Balancing Incentive Program (BIP)

5. Recent peer reviewed journal articles demonstrating the remarkable outcomes and cost savings associated with home care medicine

6. Quality end-of-life care that reduces costs and decreases hospital mortality rates

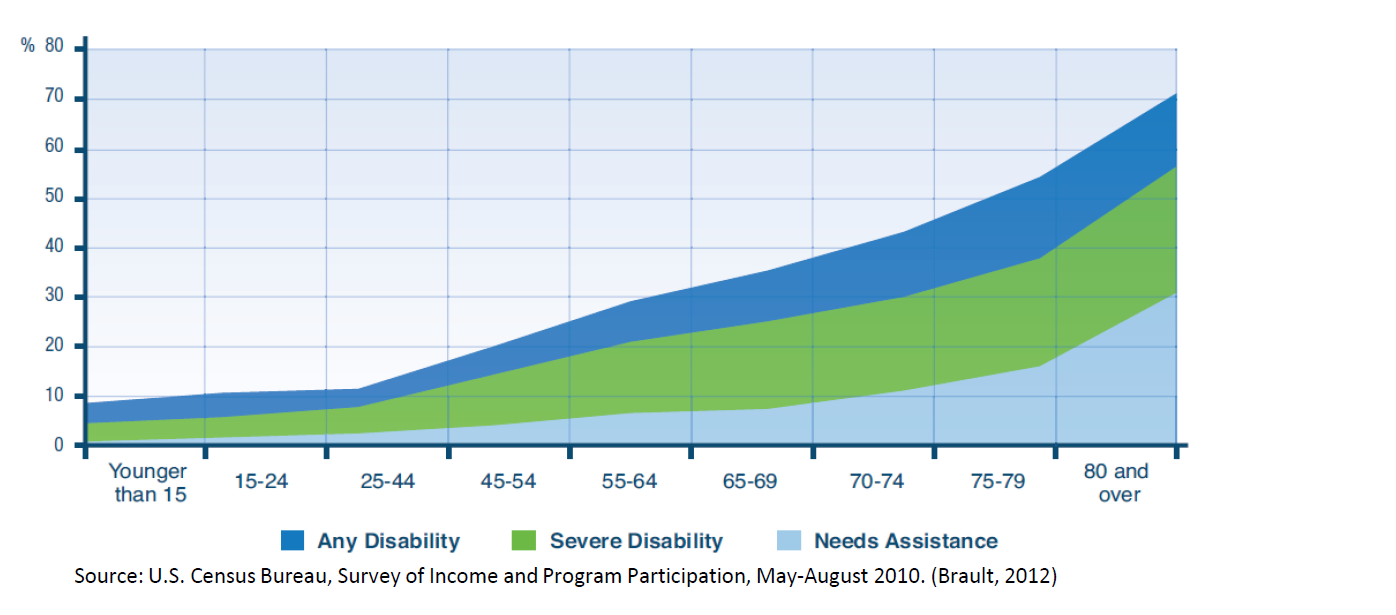

Those over 80 are the most severely disabled and in need of assistance with basic activities of daily living (feeding, walking, transferring from a chair, going to the bathroom, etc.) as seen in Figure 2. This is an exploding home-limited population. This population is the highest utilizer of costly hospital and nursing home services which home care medicine dramatically reduces.

Disability Prevalence and the Need for Assistance by Age: 2010

Note: The need for assistance with activities of daily living was not asked of children under 6 years. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Survey of Income and Program Participation, May-August 2010. (Brault, 2012)

2. The Medicare and Medicaid Fiscal Crisis

Home care medicine’s better care and cost savings offers a partial solution to the Medicare and Medicaid fiscal crisis. U.S. heath care spending reached $2.9 trillion in 2013 representing 17.4 of the Gross Domestic Product. The aged over 65 are the most rapidly growing population and are also associated with the highest healthcare costs. Medicare is facing insolvency in 2029. Medicaid was the largest component of state budgets in 2013 consuming 24.5% of total spending compared to 19.5% spent for elementary and secondary education. (1) Without a change in approach, the demand and costs for long-term services and supports (LTSS) will increase as our society ages. Medicaid is the largest payer of LTSS which includes both home and community-based services (HCBS) and nursing home care. In 2012 Medicaid spent $140 billion on LTSS representing 31.4% of Medicaid expenditures. (2) Medicaid pays for over half of the nation’s total spending on nursing homes. Home care medicine has been shown to dramatically reduce both healthcare costs and nursing home placement while enhancing both patient and caregiver quality of life.

3. Healthcare Reform: The Affordable Care Act

a. Readmission reduction

Data published in the New England Journal of Medicine, April 2009, revealed 20% of Medicare hospital discharges were readmitted within 30 days and 34% within 90 days. (3) Half of the 30-day readmitted patients had not seen a physician since hospital discharge. In 2012 Medicare started penalizing hospitals for excessive readmissions, and over 75% of hospitals have been penalized. (4) Attempts to reduce readmissions with Medicare home health (nurses, therapists, social workers, aides) have generally not been successful, with readmissions remaining high around 28%. (5)

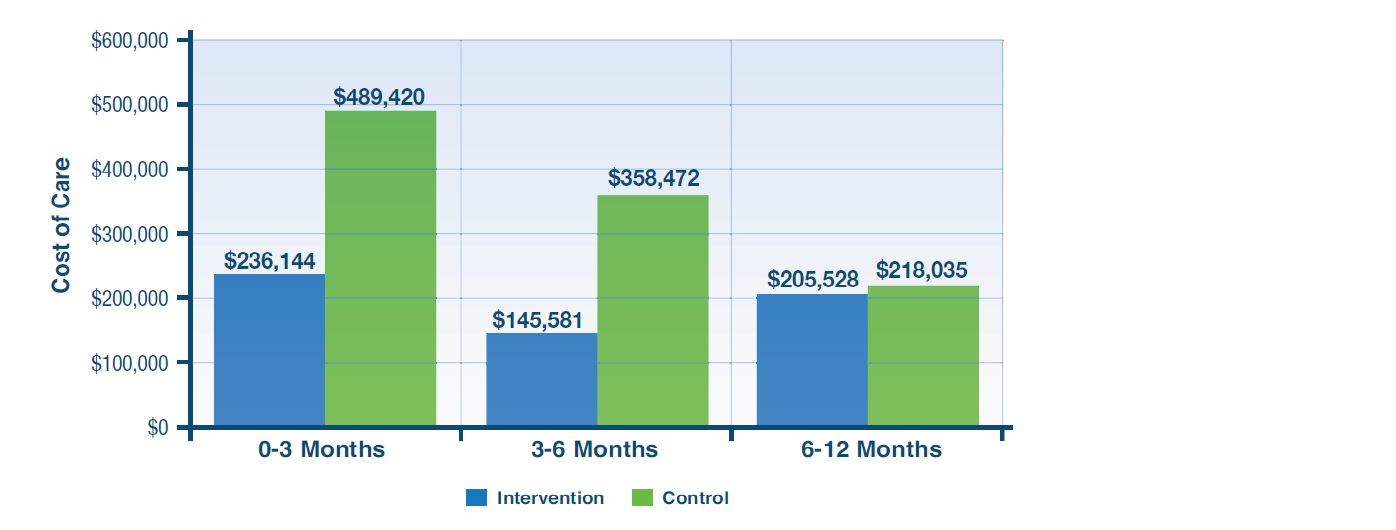

In contrast, home care medicine by doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants has shown profound effects on both reduced readmissions and healthcare costs. A study by Naylor published in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society in 2004 showed nurse practitioner house calls for three months post-hospitalization cut readmissions by more than half (23 in the house call group versus 63 in the control group). Figure 3 shows the dramatic cost savings. The house call intervention stopped at three months but benefit continued for an additional three months, with over 50% reduction in readmissions and costs vs. the control population. No further benefit was seen in the 6-12 month period three months after discontinuing the house call intervention, demonstrating the need for continued longitudinal home care medicine for this patient population.

Resource Use Among Elderly Congestive Heart Failure: Patients Who Received a Transitional Care Intervention or Usual Care, Six Philadelphia Hospitals, 1997-2011(6)

Medicare Shared Savings Programs and Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiatives

The Medicare Shared Savings Program facilitates coordination and cooperation among providers to improve the quality of care for Medicare fee-for- service beneficiaries and reduce costs. Hospitals and providers participate by creating an Accountable Care Organization (ACO). (7) The ACO’s goal is to provide higher quality and better coordinated care resulting in cost savings which are shared with the ACO. The greatest savings are generated from the highest cost patients; those with five or more chronic conditions and multiple functional deficits. This is also home care medicine’s target population. Figure 4 (8) shows that the costliest 1% of patients consume 23% of total costs at a median cost of $97,859 per patient, and the top 5% consume 50% of total costs at a median cost of $43,038 per patient.

This top tier of spending is where the greatest potential for savings is found. Home care medicine has been shown to dramatically reduce costs on these most expensive patients. U.S. Medical Management runs the Visiting Physicians of America, the largest house call program in the country. They generated over $3.6 million in savings for their Pioneer ACO program in Performance Year 2 which represented 3.75% of the total cost savings achieved under the entire ACO program nationally. (9) This statistic is remarkable considering VPA was only caring for a small fraction of the total ACO patients.

Under the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative, organizations will enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care. Traditionally under fee-for-service, Medicare financially rewards volume by making separate payments for all services furnished to beneficiaries for a single illness or course of treatment. Bundled payments for an episode of care align incentives for providers and hospitals to use resources wisely and coordinate care to reduce duplication and achieve the best outcomes. Some of the bundled payments combine hospitalization plus a predetermined 30, 60 or 90 day period of post-acute care. House calls are of great value to these bundled episodes of care in the post-acute care continuum by improving care and reducing readmissions.

3. Healthcare Reform: The Affordable Care Act

The Independence at Home Act

Listed below are the details of the three year Independence at Home Act house call Medicare demonstration program that began in April 2012. It involves one consortium and 14 independent practices and is capped at 10,000 beneficiaries.

1. IAH focuses on the highest cost Medicare beneficiaries (10% of Medicare beneficiaries with ≥ 5 chronic conditions that account for 2/3rds of Medicare spending). IAH Beneficiaries must have:

i. ≥ 2 chronic conditions

ii. Emergent hospitalization in past year + post acute care services

iii. Functional dependence (≥ 2 ADL deficiencies) and frailty

2. Holds IAH provider organizations strictly accountable for three performance standards:

i. Minimum savings of 5%

ii. Good outcomes commensurate with the beneficiary’s condition

iii. Patient/caregiver satisfaction

Savings beyond 5% are split between Medicare and the house call programs with up to 80% going to the programs if quality indicators are met. The shared savings fund the house call program’s operations and create incentives to invest in new mobile diagnostic and therapeutic technologies that can further improve care and reduce costs.

CMS released their analysis of the IAH’s first year data on June 18, 2015 and found a remarkable $25 million overall savings – an average of $3,070 per beneficiary. IAH beneficiaries had fewer 30-day readmissions, hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Quality of care increased in all measured areas such as follow-up within 48 hours of hospitalization, medication reconciliation and advanced care preferences documented. This further illustrates home care medicine’s dramatic impact on improving care while dramatically reducing costs.

4. Federal rebalancing legislation including Money Follow the Person (MFP) and Balancing Incentive Programs (BIP)

Federal rebalancing legislation provides incentives for states to increase home and community-based services to enable people to remain at home and reduce nursing home placement. The two main Programs are Money Follows the Person (MFP)

Rebalancing Demonstration Grant (authorized by Congress in the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005) (10) and, the Balancing Incentive Program (BIP- authorized by the Affordable Care Act in 2010)11. These programs provide financial and practical supports to enable patients to remain in their home or to transition from nursing homes back into the community. As of December 2013, more than 40,000 individuals across 45 states had been transitioned. This emphasis on helping nursing home eligible people remain in the community creates an added demand for home care medicine. Figure 6 shows the effect of this legislation on increasing dollars to home and community-based services.

5. Recent peer reviewed journal articles demonstrating the remarkable outcomes and cost savings associated with home care medicine

In October 2014, two peer-reviewed articles appeared in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS) that dramatically added to the evidence of the value of home care medicine. One article analyzed the Veteran Health Administration’s Home-Base Primary Care Program (HBPC) which started more than two decades ago and currently serves over 30,000 Veterans. A previous analysis of 2002 data found a 24% reduction in total costs amounting to over $9,000 savings per veteran (Table Below). HBPC financially provided four times more care in the home but still achieved cost savings secondary to a remarkable 63% reduction in hospital costs and an 87% reduction in nursing home costs. Multiplying the $9,132 savings per vet by the 11,334 in the study comes out to over $103 million in net yearly savings.

In addition to referencing the above 2002 data, the 2014 article also analyzed 2007 data and found a remarkable 59% reduction in hospital days, an 89% reduction in nursing home days and a 21% reduction in 30-day readmissions. Veterans can use both their VA and Medicare benefit and a goal of this study was to learn if the significant VA cost savings came from cost-shifting to Medicare. The cost of care was analyzed for 6,951 veterans also enrolled in Medicare in 2006. The HBPC program was associated with a 13.4% decrease in costs with a 16.7% savings to the VA and an additional 10.8% savings to Medicare. The veterans in the HBPC program received over $9,000 of additional care in the home but still had overall cost savings of greater than $6,000 per veteran principally from a 25.5% reduction in hospitalizations. The program also had the highest patient and caregiver satisfaction in the VA system. (13)

The second October 2014 JAGS article analyzed 722 HBPC patients in the Medstar Washington Hospital Center Medical House Call Program. As compared to 2,161 matched controls the HBPC program generated 17% lower Medicare costs which came to $8,477 savings per beneficiary and a remarkable yearly savings of $6.1 million. The HBPC patients had more primary care visits (house calls), more home health and more hospice. The cost savings were realized from a 9% reduction in hospitalizations and a 10% reduction in emergency department visits. (14)

6. Quality End of Life Care: Reducing costs and lowering hospital mortality rates

Seventy percent of Americans say they would prefer to die at home, but only 33.5% do. A study comparing end-of- life care in 2000 vs. 2009 found deaths at home increased (30.7% to 33.5%), deaths in the hospital decreased (32.6% to 24.6%), and hospice increased (21.6% to 42.2%). Although this data suggests that we are on the right path to fulfill people’s end of life wishes, this is a bit misleading. The same report revealed that ICU stays in the last month increased (24.3% to 29.2%), hospitalizations in the last three months of life increased (from 62.8% to 69.3%), and short hospice stays of <3 days also increased (22.2% to 28.4%) with 40.3% of those short hospice stays preceded by an ICU stay.15 This aggressive care at the end of life is not only incongruent with patients’ wishes, it is also terribly expensive. In 2010 25.1% of the $556 billion Medicare dollars went to care in the last year of life. (16)

In comparison, end of life care is much different in my own house call practice, HomeCare Physicians (Wheaton, IL), which has an annual mortality rate averaging 20-25%. Goals of care including end of life wishes are discussed early and often to best enable their fulfillment. In 2013 we had 222 deaths. 80% of patients died at home, and 74% were on hospice. The average length of stay on our house call practice was 2.1 years and the median was 1.1 years. The majority did not spend any time in the hospital in their last year of life.

One unintended consequence of quality end of life care in the home is decreased hospital mortality rates. Having 80% of 222 deaths occur at home versus 33.5% nationally resulted in 104 additional deaths at home than would be expected. My supporting hospital had 247 deaths in 2013 so enabling 104 additional deaths at home dramatically impacted their hospital mortality rate. Hospital mortality is now a part of the Medicare Quality Incentive Program that impacts hospital payments. Of note, my hospital was also one of only three hospitals in Illinois that has never received a readmission penalty (out of 127 Illinois Hospitals), and it attributes this to our house call program.

Conclusion

Home care medicine’s time has come. A perfect storm has developed creating both an economic engine and enormous demand for home care medicine. The dramatic improved care and resulting cost savings is something our society desperately needs. Currently only about 15% of the nation’s 2 million home-limited patients are receiving home care medicine. (17) Through generous donations and the support of Northwestern Medicine the Home Center Care Institute formed to help meet the demand and advance the field of home care medicine. There is significant need for workforce development and training and also development of best practices for both practice management and clinical care. HCCI looks forward to working with national leaders in home care medicine and other supporters to make this happen. There is an immense opportunity to impact the sickest and costliest patients in our society and be a major solution to our national healthcare crisis.

References:

1. The National Association of State Budget Officers. (2014, November 20). Summary: NASBO State Expenditure Report. Retrieved from National Association of State Budget Officers.

2. Eiken, S., Sredl, K., Gold, L., Kasten, J., Burwell, B., & Saucier, P. (2014, April 28). Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services And Supports in FFY 2012.

3. Jencks, S., Williams, M., & Coleman, E. (2009, April 1). The New England Journal of Medicine.

4. Rau, J. (2014, October 2). Medicare Fines 2,610 Hospitals in Third Round of Readmission Penalties.

5. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2014, December). Report to Congress: Impact of Home Health Payment Rebasing on Beneficiary Access to and Quality of Care.

6. Naylor, M., Brooten, D., Campbell, R., Maislin, G., McCauley , K., & Schwartz, J. (2004). Transitional Care of Older Adults Hospitalized with Heart Failure: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 675-684.

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014, March 11). Shared Savings Program.

8. NIHCM Foundation. (2014, November). Healthcare’s 1%: The Extreme Concentration of U.S. Health Spending.

9. PR Newswire: A UBM plc Company. (2014). U.S. Medical Management Delivers $3.6 Million in Savings for the Pioneer ACO Program. Troy, MI: PR Newswire.

10. Medicaid.gov. (n.d.). Money Follows the Person (MFP). Retrieved from Medicaid.gov. Keeping America Healthy

11. Medicaid.gov. (n.d.). Balancing Incentive Program.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2013). Medaid Persons Served (Beneficiaries), Aged, by Selected Type of Service.

13. Edes, T., Kinosian, B., Vukovic, N., Nichols, L., Becker, M., & Hossain, M. (2014). Better Access, Quality, and Cost for Clinically Complex Veterans with Home-Based Primary Care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 1954-1964.

14. De Jonge, E., Jamshed, N., Gilden, D., Kubisiak, J., Bruce, S., & Taler, G. (2014). Effects of Home-Based Primary Care on Medicare Costs in High-Risk Elders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 1825-1831.

15. Teno, J., Gozalo, P., Bynum , J., Leland, N., Miller, S., Morden, N., … Mor, V. (2013). Change in End-of-Life Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 470-477

16. Riley, G., & Lubitz, J. (2010). Long-Term Trends in Medicare Payments in the Last Year of Life. Health Services Research: Impacting Health Practice and Policy Through State-of-the-Art Research and Thinking.

17. Ornstein, K., Leff, B., Covinsky, K., Ritchie, C., Federman, A., Roberts, L., Kelley, A., Sui, A., Szanton, S. (2015). Epidemiology of the Homebound Population in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1849.

Thomas Cornwell, MD, is the Chairman and Chief Medical Officer for the Home Centered Care Institute, as well as President of the American Academy For Home Care Medicine